A new production of

Götterdämmerung opened tonight at Covent Garden, London. While we wait for the reviews to be in, I thought I would re-print this London Times article from July 14.

Wagner, like Marmite, George W. Bush and Manchester United, is a polarising force in our society. You’re either passionately devoted or implacably hostile. And once people have decided which side they’re on, there’s no shifting them.

Few artists, certainly no other composers, inspire the passionate feelings of hatred and revulsion that Wagner can provoke. But, just as the antagonism that Man U inspires among other fans only attests to their durable quality, and the antipathy that George Bush faces only underlines the importance of his challenge to traditional ways of thinking, so the strength of anti-Wagner feeling proves what his detractors cannot deny — the immense power of his music.

And music is where any encounter with Wagner should begin and end. His mature works have a power to move that no opera written before ever had. While previous operas can enchant, divert, charm, make you think, amuse and, at their best, hint at the sublime, Wagner’s work comes bounding off the stage, wrenches at your heart and tries to make a prisoner of your soul.

For many people a music that sets out so powerfully to seduce is just too much to take. When that music is written, as Wagner’s was, by a sexually manipulative and egomaniac anti-Semite, then resisting it seems almost a moral duty. But if you turn away from Wagner you’re turning your back on the chance to experience some of the most complete, and deepest, experiences you can have with your clothes on. Because Wagner’s operas use music to open up a world in which human psychology, our spiritual yearnings and even our political arrangements are all explored in a way that speaks to us, whatever our background.

Wagner’s operas differ in form from everything that went before by being complete music-dramas, in which every aspect of what goes on before us is conceived as a unified whole. Before Wagner the standard opera form was a mixture of nice incidental music, connecting plot-lines (or recitative), and the set-piece highpoints (the arias), after which everyone applauds. There is a sense of staidness, even formality, about the process.

Wagner’s operas were conceived in a wholly different way, with music, poetry, staging and plot fused so that each reinforces the other. Individual chords, or specific melodic phrases (leitmotivs), become, through their precise musical structure, symbols for characters, concepts and forces. These chords and leitmotivs can convey anything from inexpressible longing to scheming wickedness and the serenity of nature.

In the Ring the leitmotivs become one of the most important element in a multilayered experience in which the sung poetry, the performers’ acting skills and the visual cues of staging and direction all interweave to simultaneously advance the plot, reveal the inner emotional state of characters, remind us of their past interactions and suggest to us the broader allegories behind their acts.

The fusion which Wagner brings about makes his operas, and the Ring in particular, a deep intellectual as well as emotional experience. Once you begin to appreciate the depth of it, and I for one am only just beginning, you have the exhilarating feeling of knowing that this is a world to which you can return many times and find an endless amount more to appreciate, enjoy and reflect on.

Some people, of course, are put off even beginning that journey, not because they want to resist being drawn into such a seductive world, nor even because they find Wagner’s personality an obstacle, but because the whole horns and dwarves, dragons and spears palaver seems so terribly teenage. If they want an epic with swords and sorcery they’ll get The Two Towers out on DVD, because after all you can’t get CGI giants at the Royal Opera House.

But the mythic world that Wagner creates is not an adolescent escape from reality. It is a daring attempt to make genuinely universal themes artistically resonant across generations and cultures by locating them outside history. Epic and myth allow us to see our virtues, and temptations, dramatised on such a scale, and in such a way, that they speak direct to our nature. Myth, rather than distancing us from the action, enables it to cut through the specifics of our time and place and engage our souls. Wotan’s struggle between the need to observe the rule of law and his own ambition has a contemporary resonance in the politics of Britain today. But it will also have had subtly different resonances in different politics of past ages, and other nations.

Allowing the myth to breathe allows us to appreciate the universal insights about the battle between law and passion, power and love.

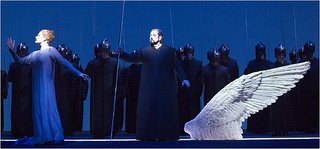

This is the second time that I have heard tenor Ben Heppner's voice crack in the middle of a Wagner opera at the MET. The first time that it happened within a personal earshot was at the matinee broadcast of Die Meistersinger a few years ago, and now he did it again Saturday afternoon, at another matinee broadcast, this time during a performance of Lohengrin. The only difference was that I heard the Meistersinger accident on the radio, but Saturday afternoon I was there. My good friend Marta and her husband Bill, members of The Metropolitan Opera Club, invited me to lunch at the club, and then to the performance. Listening to a tenor crack on the radio is one thing, being there is a truly complex musical experience.

This is the second time that I have heard tenor Ben Heppner's voice crack in the middle of a Wagner opera at the MET. The first time that it happened within a personal earshot was at the matinee broadcast of Die Meistersinger a few years ago, and now he did it again Saturday afternoon, at another matinee broadcast, this time during a performance of Lohengrin. The only difference was that I heard the Meistersinger accident on the radio, but Saturday afternoon I was there. My good friend Marta and her husband Bill, members of The Metropolitan Opera Club, invited me to lunch at the club, and then to the performance. Listening to a tenor crack on the radio is one thing, being there is a truly complex musical experience.