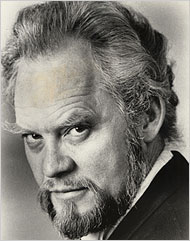

The great American bass-baritone Thomas Stewart died this week. He passed away after making par on a golf course. He had turned 78 last month.

The great American bass-baritone Thomas Stewart died this week. He passed away after making par on a golf course. He had turned 78 last month.Here is the obituary, written by Tim Page, from The Washington Post.

Thomas Stewart died just the way many of us would choose to go -- instantly, in the company of the woman he loved, and on the golf course, immediately after making par.

The great American bass-baritone, who had turned 78 last month, was on the links near his home in Rockville late Sunday afternoon. "He had had heart surgery earlier this year and had not been feeling well for some time, but he was getting along, still active, cheerful and doing things," soprano Evelyn Lear, Stewart's wife of more than half a century, said yesterday. "We went out to the course, played for a while, he made par, and then suddenly turned around and fell backwards. I tried to resuscitate him, but he didn't respond."

Stewart was rushed to a hospital, where he was pronounced dead from a massive heart attack.

Onstage, Stewart was a booming, magisterial and frankly awe-inspiring presence (he was, for example, the first American in history to sing the Norse god Wotan in Wagner's complete "Ring" cycle at Bayreuth). Offstage, he was friendly, kind, self-effacing and absolutely unpretentious.

Will Rogers used to say that he never met a man he didn't like; in a similar spirit, I can affirm that I never knew anybody who didn't like Tom Stewart. Yesterday was a day of mourning in the music community -- hours on the telephone, shocked and saddened e-mails floating through cyberspace.

Matthew Epstein, the director of the worldwide vocal divisions at Columbia Artists Management, who knew Stewart for 40 years, called him "just about the most marvelous person in the world, and you'd get agreement with me from everybody from the legendary singers he worked with early in his career, such as Birgit Nilsson and Jon Vickers, to the young people he nurtured as part of the Evelyn Lear and Thomas Stewart Emerging Singers Program."

This last endeavor was especially dear to both Lear and Stewart. In company with the Wagner Society of Washington, the two provided musical guidance for more than 70 aspiring Wagner singers since 2000, presenting two concerts each year.

"Why were the works of Wagner so important to me as an artist?" Stewart asked in an essay he wrote to accompany a recording. "It's because of the marriage of word and music, something every composer seeks to achieve but few accomplish with such perfection. Being a singer who becomes completely absorbed in the text he is singing, I naturally felt an affinity for this aspect of Wagner's art."

Epstein called Stewart a perfect example of what an American singer should be -- "deeply musical, able to sing in many different styles and languages, a wonderful actor with a fabulous vocal technique. He could sing Wotan, and then he could turn right around and sing a comic Italian part such as Verdi's Falstaff. Every director he ever worked with thought he was a great actor. And every musician he ever worked with knew he was a great singer."

Stewart was born Aug. 29, 1928 in San Saba, Tex. After some early studies in electrical engineering in Waco, he moved to New York, where he studied with Mack Harrell at the Juilliard School. After graduation, he sang with the New York City Opera and the Lyric Opera of Chicago, where he took on the bass role of Raimondo in Maria Callas's American debut in Donizetti's "Lucia di Lammermoor."

He married Evelyn in 1955. The two moved to Berlin, where they sang at the State Opera and then throughout Europe, before returning home to the United States for long and distinguished careers with the Metropolitan Opera. For more than a decade, Lear and Stewart have divided their time between Rockville and Florida.

They made many recordings together, a number of which are available on the VAI label; a five-CD retrospective was recently issued on Deutsche Grammophon. Stewart's own favorite disc was one that he made of Wagner's complete "Die Meistersinger von Nuernburg" with the conductor Rafael Kubelik and the soprano Gundula Janowitz that was taped in the late 1960s but, for contractual reasons, never issued until the 1990s.

Tom and Evelyn came over for dinner at my home in Baltimore in early August. He was clearly tired but was grand company throughout the evening, touching on several favorite subjects -- his interest in alternative medicine, his amused skepticism toward any form of religion, news of mutual friends in New York and Washington. After considerable prodding, he favored us with an impromptu, heartfelt and achingly beautiful a cappella rendition of the old folk song "Shenandoah," which rings through my ears as I write this.

It was a performance of depth, strength, courage, love -- all qualities exemplified by Thomas Stewart. The gratitude felt by his friends and admirers is immense.