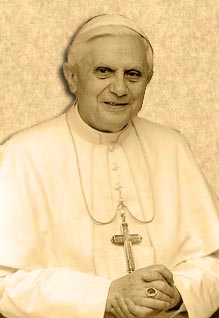

I knew it was going to happen, and I called it at the end of my entry for April 8. As the winner of the Papal election, the former Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, now Pope Benedict XVI, cut a unique figure during John Paul II's funeral. As he presided at the mass for the late Pontiff, there was a feeling that it was a done deal. A week later he was elected Pope after one of the shortest conclaves in recent history.

Since his election much ink has been spilled about Ratzinger's past. Pictures of young Josef in his Hitlerjunge uniform seemed to be everywhere, and the London Times reminded everyone that "unknown to many members of the church ... Ratzinger’s past included brief membership of the Hitler Youth movement and wartime service with a German army anti- aircraft unit." The article, written a few days before his election, goes on to report that "in 1937 Ratzinger’s father retired and the family moved to Traunstein, a staunchly Catholic town in Bavaria close to the Führer’s mountain retreat in Berchtesgaden. He joined the Hitler Youth at age 14, shortly after membership was made compulsory in 1941." Also, we learn that "two years later Ratzinger was enrolled in an anti-aircraft unit that protected a BMW factory making aircraft engines. The workforce included slaves from Dachau concentration camp."

Pope Benedict XVI should be a very busy man from now on. He needs to heal a Catholic Church (in particular the American Church) which has been wounded. He needs to overcome his past, which is tied to the history of his country, and he needs to shed the tough outer skin he developed as John Paul II's defender of the faith. He has to go from being the German rottweiler to becoming the German shepherd -- the Shepherd of the flock, that is.

The following article, written by Jane Kramer, appeared in the May 2 issue of The New Yorker magazine. Although it presents a largely negative reaction to last week's events in Vatican City, her ideas are interesting, and her writing style fresh and informative.

"Holy Orders" by Jane Kramer

Cardinals of the Church of Rome do not normally hold press conferences to spin their choices, but that is precisely what many of them did last Wednesday, less than a day after they named Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, the Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, and arguably the most powerful person in the Vatican, to St. Peter’s chair. They wanted the world to know that Ratzinger has a “great heart,” that he is “compassionate,” “collegial,” even “shy”—that, in fact, it was shyness and humility that had made him seem so strict and pitiless in the job of doctrinal enforcer that he held for the past quarter of a century.

In his homily to his fellow-cardinals, on the first morning of their conclave, Cardinal Ratzinger had warned that modern society was threatened by a “dictatorship of relativism.” But it might have been more accurate to say that it is threatened by a dictatorship of absolutisms, including his own. This is a world in the tightening grip of orthodoxy, of literal “truths” and crusading certainties, and early last week it was the hope of many Catholics that the Church would begin to break that grip and return to them the right to exercise their own consciences on matters that do not concern faith so much as the realities of their intimate lives: sexuality, celibacy, choice, the use of condoms in aids-ridden Africa, the use of birth control in the favelas and shantytowns of Central and South America, the acknowledgment that stem-cell research might conceivably be a gift from God.

The question of God and conscience, or, rather, the relation between God and conscience—the central question of Vatican II, and, as such, the source of immense hope to young Catholics in the nineteen-sixties and seventies—was so “deconstructed” (to risk a relativist term) in the twenty-six years of John Paul II’s papacy that raising it now constitutes a kind of doctrinal heresy. Ratzinger maintained, with his friend and predecessor, that a well-ordered conscience is one that submits to the authority of the magisterium. So it is understandable that today those Catholics are asking who exactly is, and was, Joseph Ratzinger. Was he the Pope’s man, the unbending instrument of John Paul II’s insistent orthodoxy, or was he, at least in part, the motor of that orthodoxy, especially in the Pontiff’s last years?

Most Popes of the last century—even John Paul II, for all his groundwork as a priest in Communist Poland—were elevated to that office from relative anonymity. Ratzinger does not have that advantage. He has been well known to Catholic intellectuals since the nineteen-seventies, when he battled Hans Küng, the liberal Swiss theologian and his mentor at the University of Tübingen, on questions of doctrinal dissension, and, as Archbishop of Munich, was instrumental in having Küng barred from teaching Catholic theology. And, of course, he has been very well known to most Catholics since the early eighties, when the Pope installed him at the Vatican. His agenda, or his orders, were always clear. During his first ten years as Prefect, the Jesuits were censured for challenging papal teachings on contraception, parts of their constitution were suspended, and their Vicar General, Vincent O’Keefe, a passionate advocate for social justice, was removed. The reactionary lay order Opus Dei was transformed into a “personal prelature” accountable directly to the Pope. The dioceses of progressive Latin-American bishops were gerrymandered out of existence, liberation theologians like Leonardo Boff were called to Rome and silenced as “Marxists” (they were, more accurately, Christiancommunitarian evangelists), and the priests they had trained, who were responsible for an ebullient Catholic revival in Latin America, were ordered back into the fold of tradition and obedience. The relative autonomy of the North American bishops’ conference was ended, and its most progressive members—most famously Cardinal Joseph Bernardin, of Chicago—were marginalized.

If the Vatican’s project in the eighties was to purge its clergy, its nineties project was to purge its teachings of ambiguity. The dogma of papal infallibility, which dates only from 1870, has been invoked just once since then, in 1950, when Pius XII proclaimed the “truth” of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary. But in the years of John Paul II’s papacy there was a conflation of the notion of infallibility and what the Church calls “definitive teachings.” The result was that John Paul II’s teachings often carried the imperative of infallibility, and Cardinal Ratzinger’s theological imprimatur on those teachings, together with his power to enforce them, effectively ended the discussion.

These issues were more important to the cardinals than the new Pope’s age or whether he was Italian, or European, or from Latin America or Africa. There are a hundred and eighty-three cardinals, but no cardinal over the age of eighty may vote, and, of the hundred and fifteen who did, all but two owed their appointments to John Paul II. It was probably never in doubt whom they would choose. Joseph Ratzinger speaks for them, and whatever he says about “waves” battering at the boat of the true faith—globalism, feminism, individualism, desire, homosexuality (“an objective disorder”), demands for the ordination of women, mysticism, “gravely deficient” sects, Turkish Muslims in Christian Europe—those words put a full stop to the opening up of the Church of Rome that we still call Vatican II. In the past few days, Benedict XVI has promised the world dialogue and reconciliation, but at the same time he has reappointed the Vatican team that, with him, brought us the spectacle of suffering and death that ended with the funeral of John Paul and secured the veneration, if not the speedy sanctification, of that faithful and controlling Pontiff. (“This is a long way from three people at the foot of the Cross,” one ex-Jesuit remarked last week, not long after Benedict XVI appeared for the first time in his papal vestments.) Most of the Cardinals wanted a continuum of that always spectacular reign. And they wanted a continued enforcement of its most conservative dicta—which may be why they are talking now about cutting their losses for the advantages of a smaller, “purer” Church. But, from what we know, the early Church was a place of risk and debate. They should remember that, too.

1 comment:

Click here to learn more about audi allroad

Post a Comment